Scientists are hoping to “re-introduce” the iconic carnivorous marsupial into existence with the help of gene-editing technology.

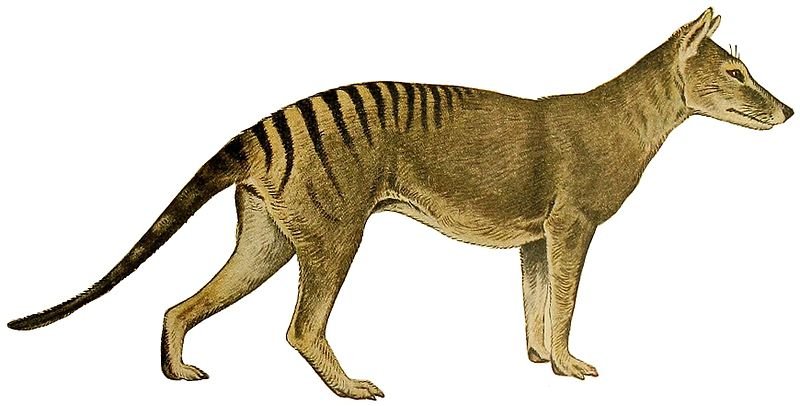

Dog-like creatures that had pouches on their backs roamed the mainland of Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania millions of years ago. These striped carnivores hunted a wide variety of prey, including kangaroos, birds, and small rodents. However, the European colonists who arrived in the South Pacific in the 1800s and 1900s viewed these marsupials, known as thylacines, with distain. The settlers were incentivized to kill the animals by the government, so they began doing so in a methodical manner.

The population of thylacines, also called Tasmanian tigers or Tasmanian wolves, started to decrease until the year 1936, when the last-known member of the species, an animal named Benjamin who was kept at a zoo, passed away in his cage.

Genetic restoration-The Fairytale Science

The Texas-based genetics start-up Colossal Biosciences this week revealed another ambitious new project to bring thylacines back from the brink of extinction. Last year, the company announced plans to bring back the woolly mammoth from the brink of extinction. In the hopes of one day reintroducing thylacines to Tasmania in an effort to rebalance the ecosystem there, the organisation has teamed up with scientists and is investing in a laboratory that will be dedicated to resurrecting extinct thylacines.

Skepticism in large amounts has been generated as a result of the project. According to Jeremy Austin, an evolutionary biologist working at the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, the concept represents “fairytale science.” Liam Mannix of The Sydney Morning Herald quotes Austin as saying this.

Austin tells the Morning Herald that it is “pretty clear to people like me that thylacine or mammoth de-extinction is more about media attention for the scientists and less about doing serious science.” “It’s pretty clear to people like me that thylacine or mammoth de-extinction is more about media attention for the scientists,” Austin says.

The company is collaborating with researchers at the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research Lab at the University of Melbourne, which was established earlier this year thanks to a donation of $5 million. According to the Morning Herald, Colossal will make an additional investment of $10 million, in addition to providing equipment, lab access, and staff members, in order to assist the new lab in accelerating its efforts to de-extirpate the thylacine.

Gene Editing: The Technology & Process

In what specific ways do the researchers intend to bring extinct animals back to life? with extreme caution. They will begin by sequencing the thylacine’s genome using DNA that has been stored safely for several decades. After that, they will carry out the same procedure on a small marsupial known as the fat-tailed dunnart, which is considered to be one of the thylacine’s closest living relatives.

After analysing both genomes, the researchers plan to use gene-editing technology to bring the DNA of a fat-tailed dunnart cell closer to that of a thylacine. This will be done after they have compared the two genomes. Their plan is to stimulate embryonic growth after inserting the nucleus of the cell into the egg of a fat-tailed dunnart and then watching it develop.

They believe that this will result in the development of an embryo similar to that of a thylacine in either an artificial womb or the uterus of a dunnart surrogate mother, where it will gestate for up to 42 days. If everything goes according to plan, then the world will soon welcome the arrival of a baby that is similar to a thylacine. Kate Evans of Scientific American reports that researchers believe they can create an animal that is approximately 90 percent similar to the thylacine within the next decade. However, their ultimate goal is to create an animal that is 99.9 percent similar to the thylacine.

According to Ben Novak, the lead scientist for the de-extinction nonprofit Revive & Restore, who spoke with Yasemin Saplakoglu of Quanta Magazine in May, de-extinction is impossible in the strictest sense of the word. He told the publication, “You can never bring something that is extinct back,” and I quote: “It would be impossible.” According to what Quanta wrote, most of these businesses have the intention of developing a substitute creature that can take the place of the extinct species in the ecosystem.

Colossal wants to work with conservation groups and Indigenous peoples of Tasmania in order to release new thylacines into the wild in Tasmania if it is successful in creating new thylacines. The researchers think that thylacines, which were once Tasmania’s most dangerous predator, could help control the overpopulation of animals such as wallabies and kangaroos and hunt sick animals to stop the spread of diseases.

The progression and the opposition of gene editing technology.

According to Andrew Pask, an epigeneticist at the University of Melbourne who is leading the project and providing commentary to CNN’s Katie Hunt, “our ultimate goal with this technology is to restore these species to the wild, where they play absolutely essential roles in the ecosystem.” Our greatest wish is that you will be able to meet up with them in the wilds of Tasmania at some point in the future.

The project has been met with opposition from a number of different quarters, despite the fact that there are high hopes for the return of thylacines to Tasmania. A lot of things need to go right. Some sceptics believe that the researchers ought to be speaking with Indigenous Australians right now, before moving forward with the project in a more serious manner.

Others have voiced their concern that the prospect of bringing an extinct species back from the brink of extinction will divert resources and attention away from the protection of endangered species that are still in existence. According to an article published in Scientific American, a number of researchers believe that it is simply not possible to modify the genome of the fat-tailed dunnart so that it resembles that of the thylacine. This is because the two species are extremely distinct from one another and have evolved in separate directions over a period of millions of years.

But still other people are concerned about the way animals were treated during the course of the research project, as well as the eventual quality of life of any proxy thylacines that end up being created. There are also ethical concerns raised by certain scientists regarding genome editing in general.

According to Carol Freeman, an interdisciplinary researcher at the University of Tasmania, who spoke with Scientific American, “the whole discourse is about bringing this animal back, but the welfare of the individual animals isn’t really talked about.”